McNeill Bay is an indentation on the south coast of Oak Bay District. The bay is flanked by Gonzales Hill on the west and Anderson Hill on the east.

It’s an extraordinarily scenic area, with magnificent views from the hills …

McNeill (Shoal) Bay from Gonzales Hill, circa 1906-10. Real-photo postcard; collection of Dr. Richard Moulton.

McNeill (Shoal) Bay from Gonzales Hill, circa 1906-10. Real-photo postcard; collection of Dr. Richard Moulton.

“Shoal Bay from Gonzales Hill,” postcard from watercolour by Edward Goodall, after 1962. Used by kind permission of Richard Goodall.

“Shoal Bay from Gonzales Hill,” postcard from watercolour by Edward Goodall, after 1962. Used by kind permission of Richard Goodall.

And a waterfront drive where Victorians have been taking out-of-town visitors for more than a century …

“Oak Bay Drive, Victoria, B.C.” Litho postcard circa 1906-10. Author’s collection.

“Oak Bay Drive, Victoria, B.C.” Litho postcard circa 1906-10. Author’s collection.

The area shows up on the archaeological record … [separate article to come] … evidence of villages … Boas’s names in article on Lkwungen … Duff’s names in The Fort Victoria Treaties … A cairn recently installed on Anderson Hill brings long-overdue recognition of the ancient presence of First Nations. These cairns can be found in various locales around Oak Bay — thanks hugely to the efforts of Marion Cumming and Heritage Oak Bay.

The first written evidence of human use of the area is Spanish … [separate article to come] … exploratory parties in 1790 and 1791 … They named Punta de San Gonzalo, which endures to this day as Gonzales Point — it’s presently occupied by the 9th tee of the Victoria Golf Club.

In 1850, a year after the Colony of Vancouver Island was established, the Hudson’s Bay Company bought land from local First Nations, and they determined that the owners of the south coast of what we call Oak Bay was the Chilcowitch family.

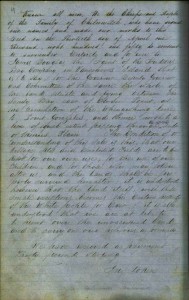

The following year, HBC Governor Sir John Pelly wrote to the British Colonial Secretary Earl Grey, “I have the honour to report to your Lordship that the Hudsons Bay Company have made the following Sales of land in Vancouver’s Island at the price of One Pound per Acre viz …”

Public Offices Document. Pelly to Grey. 5120, CO 305/3, p. 373, registered 13 June [1851]. On The colonial despatches of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1846-1871 website.

Public Offices Document. Pelly to Grey. 5120, CO 305/3, p. 373, registered 13 June [1851]. On The colonial despatches of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1846-1871 website.

There for possibly the first time in writing is mention of W. H. McNeill’s purchase of property. (More about the purchase in the article Whose Gonzalo Farm is That?)

![CALL NUMBER: A-01629 Catalogue Number: HP003803 Photographer/Artist: Spencer, Stephen Allen, 1829? - 1911 Date: [ca. 1860] Accession Number: 193501-001](http://oakbaychronicles.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/McNeill-WH-port-202x300.jpg) William Henry McNeill, circa 1860. Photographed by Stephen Allen Spencer. BC Archives call no. A-01629, catalogue no. HP003803. Courtesy Royal British Columbia Museum Corporation.

William Henry McNeill, circa 1860. Photographed by Stephen Allen Spencer. BC Archives call no. A-01629, catalogue no. HP003803. Courtesy Royal British Columbia Museum Corporation.

In that modest way the McNeill family became the second to settle in Oak Bay, by the bay that eventually took their name. (Some still call it Shoal Bay.)

History has not been kind to William Henry McNeill. His life and work have been seriously misrepresented by his grandson (see McNeill’s Kygarney Summer) and more recently by his only biographer. Captain McNeill has not taken his rightful place among the province’s founders. Hopefully this chronicle will bolster the reputation of an extraordinary, even legendary, British Columbian.

In tracing the genesis and fortunes of this large family, we will linger over McNeill’s second wife Neshaki, latterly Martha, an Oak Bay resident even more interesting and colorful, if that is possible, than McNeill himself.

Singularly among Oak Bay’s earliest settlers, McNeill descendants live in Oak Bay to this day.

1. Family of origin

William Henry McNeill was a fur trader out of Boston, Massachusetts.

He was born on July 7, 1801.

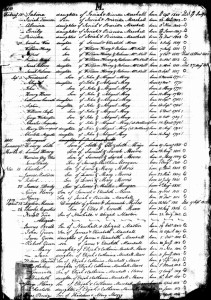

This handwritten ledger of unknown provenance (a parish register?) gave the birth dates of McNeill and his four siblings and recorded the deaths of two.

Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook).

Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook).

The identities of his family members match McNeill’s information in letters written circa 1846-52* about his widowed mother Rebecca, who removed to Charlestown, brother Frederick, who joined the US Marine Corps, and sister Sarah, who married in 1851.**

* WHM letter to Sir George Simpson, September 3, 1846, cited in The letters of John McLoughlin, from Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee, third series, 1844-46. Edited by E. E. Rich. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1944, p. 318.

** At age 41 Sarah Rebecca McNeill married George Dennie, a 48-year-old widower with five children, in Boston. The 1839 directory listed “Dennie (George) & Boardman (B. G. jr.), leather and hides, 23 N. Market. D’s h. 37 Blossom;” in the 1850 census he gave his occupation as leather dealer. Sarah died in 1890; the death registration gave her father William’s birthplace as Canada.

I have not been able to verify assertions that the McNeills came to America from Scotland, nor the suggestion they immigrated from Ireland. What is known is that William Henry’s father was also William Henry McNeill; he was born in 1764/65, based on the age (49) given on his 1814 death record.(1) Nothing certain comes to light about his lines. In the realm of conjecture, however, and on the assumption that there’s an element of truth in every family legend, we can construct a possible narrative. The register of the Presbyterian Church in Long Lane, later known as the New Federal Street church, and after 1860 as the Arlington Street Church, commemorates the marriage of William MacNeal and Katharine Morrison on September 18, 1745. (2) They had at least six children, the eldest named William, baptized August 24, 1746.(3) Catherine McNeil, 42, wife of William, died on March 23, 1761.(4) On February 4, 1862, William MacNeal and Ann Eliot were married.(5)

1. Deaths and Internments in Boston. Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988. Original data: Town and City Clerks of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Provo, UT: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook). Also in Deaths Registered in the City of Boston (Listed Alphabetically) From 1801 to 1848. ¶ 2. Arlington Street Church, Boston, MA. Records, 1730-1979. bMS 4/2 (2). Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School, Cambridge, Mass, p. 82, left panel. ¶ 3. ibid, p. 14 left. ¶ 4. Deaths registered in the city of Boston (Listed Alphabetically) from 1700 to 1800 Inclusive. Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988. ¶ 5. Arlington Street Church records, p. 78 right.

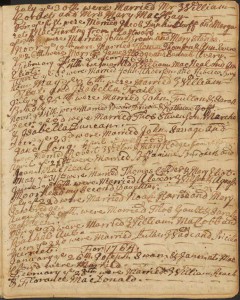

From the register of marriages in the Presbyterian Church in Long Lane (Arlington Street Church), 1762. Courtesy Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School.

From the register of marriages in the Presbyterian Church in Long Lane (Arlington Street Church), 1762. Courtesy Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School.

The minister officiating at the wedding is identified as Rev. John Moorhead.(1) Moorhead was an Ulsterman from Belfast, and the church in Long Lane was a focal point for Scotch Irish immigrants.(2) William McNeill shows up as an administrator of Rev. Moorhead’s estate, sometime during or after 1773.(3) In 1780 William McNeill is accounted a ropemaker in Boston.(4) In 1789 we find “McNeil Wm & Son, rope-makers, Fort Hill, Cow Lane.”(5) In the 1790 federal census, William McNeill is the head of a household numbering four free white males of 16 years and upwards, five free white females.(6) Finally, William McNeil turns up in “A list of all the families belonging to the Congregation in Federal Street, Boston, & of the number in each, inoculated for the small pox. Begun August 30, 1792.”(7) The family members numbered six.

1. “From the record of the Presbyterian Church in Long Lane — Now New Federal Street.” Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988. ¶ 2. The New England Historical & Genealogical Register and Antiquarian Journal, Vol XXVI (1872), p 420. ¶ 3. Scotch Irish Pioneers in Ulster and America by Charles Knowles Bolton. Boston: Bacon and Brown, 1910, p. 171. ¶ 4. Assessors’ “Taking Books” of the Town of Boston, 1780. Boston: Reprinted from the Bostonian Society’s Publications, 1912, p. 44. ¶ 5. First Boston Directory, 1789. ¶ 6. Ancestry.com. First Census of the United States, 1790 (NARA microfilm publication M637, 12 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C. ¶ 7. Arlington Street Church (Boston, Mass.); Records, 1730-1979; Jeremy Belknap’s list of families in the parish, with information about “inoculation” of members, and records of deaths from smallpox in Boston, 1702-1792. bMS 4/9 (3). Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School, Cambridge, Mass.

Nothing links William Henry McNeill, Senior with William MacNeal the parishioner of the church in Long Lane. (Its baptismal records end abruptly in 1760 and do not resume until 1786.) It’s not even certain that the William MacNeal who married Katherine Morrison later married Ann Eliot. An axiom of north European genealogy, moreover, holds that names are “handed down” through the generations of a family. Given the names of William Henry McNeill’s children, we would expect to find his uncles named Henry, Alfred, Frederick or Donald — not Daniel, Archibald and John. Alternatively, there’s the possibility that William Henry, Senior was born in Canada, as stated in Sarah Rebecca Dennie’s 1890 death registration (footnoted above), which unlinks the narrative from the McNeills of the church in Long Lane.

It is intriguing, though, that William’s second marriage occurred so near the estimated time of birth of William Henry, Senior. I’m inclined to employ Occam’s razor and choose the simplest explanation — that the William McNeill who married twice was William, Senior’s father and the rope-maker in the Telling Book and Boston Directory and head of the household in the census and smallpox enumeration. And entertain the possibility that the McNeill family were Ulster Scots who immigrated from Northern Ireland.

The mother of our subject, William Henry McNeill, Junior, was Rebecca Conant, and she was born in 1771/72, based on the age (75) given on her 1847 death record. The same document records that she was from Charlestown, the community (established in 1629) on the north shore of the Charles River.

![Publisher: Wayne, Caleb Parry Date: 1806 Dimensions: 23.0 x 34.0 cm. Scale: [ca. 1:51,000] Call Number: G3764.B6 1806 .B67](http://oakbaychronicles.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Boston-map-1806-colour-crop-213x300.jpg) Boston with its Environs (detail), published by Caleb Parry Wayne, Philadelphia, 1806. Courtesy the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Boston with its Environs (detail), published by Caleb Parry Wayne, Philadelphia, 1806. Courtesy the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Ample documentation of the Conant family in Charlestown is available online. It reveals a perplexity about her parentage. Rebecca the daughter of William Conant and Sarah Morecock was baptised on December 22, 1772. Rebecca the daughter of Samuel Conant and Rebecca Coffin was baptised on September 10, 1773.

The Genealogies and Estates of Charlestown in the County of Middlesex and Commonwealth of Massachusettts, 1629-1818 by Thoma Bellows Wyman, [Vol 1,] A-J. Boston: David Clapp and Son, 1879, pp. 232-3.

Curiously, the vast A History and Genealogy of the Conant Family in England and America, Thirteen Generations, 1520-1887 by Frederick Odell Conant, M.A., Privately Printed, Portland [Maine], 1887, uses the same source but omits Rebecca the daughter of Rebecca and Samuel Conant.

As to which Rebecca married William Henry McNeill, my guess is the daughter of Sarah and William Conant, for two reasons: her baptism is closer to the estimated date of birth of William McNeill’s widow; and her only daughter was named Sarah Rebecca, which strongly suggests her mother’s name was Sarah.

William Conant (c. 1727-1811) and Samuel Conant (1730-1802) were brothers. Samuel was a baker with an extensive estate, mostly in land. William was a selectman of Charlestown 1767-71 and lieutenant colonel in the revolutionary militia. “[A]t a meeting of the officers of the First Regiment of militia, held Nov. 29, 1774, Thomas Gardner was chosen Colonel, Wm. Bond, Lieut. Col. and William Conant, 2nd Lieut. Col. (Boston Gazette, Oct. 19, 1772, and Dec 5, 1774).”* He was afterwards appointed lieut. colonel of the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment.**

* A History and Genealogy of the Conant Family, p. 238.

** Year Book of the Societies Composed of Descendants of the Men of the Revolution, by Henry Hall, New York: Republic Press, 1890, p. 209.

Assuming William Conant to be Rebecca’s father, a window opens on one of the most famous events in American history, “the midnight ride of Paul Revere.” The History and Genealogy of the Conant Family recounts the narrative of Paul Revere’s ride from a point of view at odds with Longfellow’s poem on the crucial matter of who hung two lamps in the North Church steeple and for whose information:

It was with Col. Conant that Paul Revere planned the hanging of the signal lanterns in the steeple of the North Church, to give warning of any movement of the British army toward Concord, where the patriots had gathered their stores. Revere says: “I agreed with a Col. Conant and some other gentlemen, that if the British went out by water, we would show two lanterns in the North Church steeple, and if by land, one, as a signal.” It seems that Dr. [Joseph, later General] Warren had sent Revere with a message to [John] Hancock and [Samuel] Adams, in Lexington, where they passed their nights while attending the sessions of the Provincial Congress, at Concord. On his return from this errand he met Col. Conant, at Charlestown, and made the arrangement to show the signals on any movement of the British. On Tuesday evening (Apr. 18, 1775), about ten o’clock, Dr. Warren discovered the movement of the troops, “sent in great haste,” says Revere, “for me, and begged that I would immediately set off for Lexington.” He went at once and directed the hanging of the lanterns in the steeple; took his boat and rowed over to Charlestown. He says: “They landed me on the Charlestown side. When I got into town I met Col. Conant and several others; they said they had seen our signals. I told them what was acting, and went to get me a horse ” (Mass. Hist. Col., 1st Series, Vol. V., p. 107). He then set out on his “midnight ride.” From the above statements the historical inaccuracies of the poem are apparent. The lanterns were not displayed for Revere’s information—for he already knew all they were intended to convey—but for the information of Col. Conant and his friends. …

History and Genealogy of the Conant Family, p. 238. The quoted statements of Paul Revere are from a letter written c. 1798 at the request of Jeremy Belknap, corresponding secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and reproduced in both facsimile and transcript on the society website, along with Revere’s deposition before the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, c. 1775, in which there is no mention of Col. Conant.

In sum, Rebecca Conant descended from a family that immigrated to Massachusetts in 1623-4 and whose paterfamilias Roger Conant (1592-1679) is accounted the founder of Salem and the first governor of Massachusetts. Rebecca was of the third generation of Conants to live in Charlestown, where at this time they were apparently fairly prosperous.

William McNeill and Rebecca Conant married on September 23 (or 22), 1800. As noted in the register above, William was the eldest of their five children.

In 1802, William, Senior was appointed an “Auchtioneer” by the Boston Selectmen (town council). The one-year license was renewed in 1803. In 1804 he disappeared from the list, and evidently did not return to that line of work. Nor does he show up in the 1805 Boston Directory.

A Volume of Records Relating to the Early History of Boston Containing Minutes of the Selectmen’s Meetings, 1799 to, and including, 1810. Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1904.

In 1810 William, Senior gave his occupation as “hayweigher,” and they lived on North Allen Street in Boston.

From The Boston Directory, published by Edward Cotton, September 1810. Courtesy The Boston Athenæum.

From The Boston Directory, published by Edward Cotton, September 1810. Courtesy The Boston Athenæum.

Map of Boston in the state of Massachusetts

Map of Boston in the state of Massachusetts

by John Groves Hales, 1814 (details). Reproductions courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Here’s what the area looks like today, courtesy Google Maps:

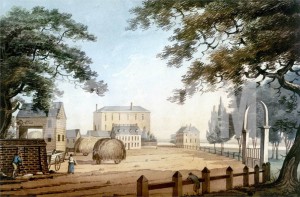

The hay scales and haymarket were on West Street, across from the Common, a few blocks south of North Allen. There’s a capital view of the hay scales in a watercolour painted a little before McNeill’s time:

The Haymarket Theatre, Boston by Archibald Robertson, September 28, 1798. Collection of the Boston Public Library. Thanks to art.com for the borrow of the image. The view is to the south looking down Tremont Street from the intersection of West Street; the Boston Common is to the west, at right. The theatre was the large building in the distance; the hay scale was presumably the building on the near left, with what looks like a drive-through for hay wagons. About the operation of the hay scale, or its role in the commerce of the town, nothing comes to light.

The Haymarket Theatre, Boston by Archibald Robertson, September 28, 1798. Collection of the Boston Public Library. Thanks to art.com for the borrow of the image. The view is to the south looking down Tremont Street from the intersection of West Street; the Boston Common is to the west, at right. The theatre was the large building in the distance; the hay scale was presumably the building on the near left, with what looks like a drive-through for hay wagons. About the operation of the hay scale, or its role in the commerce of the town, nothing comes to light.

William, Senior had a rough ride as hayweigher, to judge from the minutes of the Boston Selectmen. He was appointed to the job on January 10, 1810. Things went okay for a while:

At a Meeting of the Selectmen March 20th, 1811 … The accounts of the hay Weigher were exhibited for the year ending Jany 1st.—by which it appeared, that the gross Amount of Receipts for Weighing were $1191 … two thirds of which being allowed for his services $ 794 … remains for the Town’s proportion $397 … from which deduct expences, repairs &c $180.59 … leaves the net proceeds which he has paid to the Town Treasurer per. his certificate $216.41

Voted, That in future the hay weigher settle his accounts once a quarter with the Selectmen & pay the balance to the Town Treasurer.

Voted, That in future, all expenditures for repairs of the Hay Scales be done under the direction of & by order of one of the board; & that E. Oliver Esq be desired to attend to this business the ensuing year.

On April 17, 1811 he rendered his quarterly account and paid the town $92.87 against earnings of $211.11. But:

A Remonstrance or complaint against Mr. McNeill in his office of hay weigher was read—and agreed that the first signer should be notified to appear on Wednesday next to explain his cause of complaint.

And on April 21 it was recorded that

Several complaints having been received of errors made by the hay weigher in his tickets of hay, compared with the tickets for the same loads weighed in Dearborn’s patent platform balance—Mr Oliver was desired to employ some suitable person, with the sealer of weights to examine the Towns Scales, & have them made correct.

By March 10, 1813 the wheels had come off McNeill’s hayweighing career:

Mr. McNeill, hay weigher, having exhibited his accounts to January 1st. the same were examined, it however appeared that he had not paid to the Treasurer the balance of the year 1811, or any portion of the proceeds of 1812—it was ordered that the Chairman inform Mr. McNeill that unless those sums are paid before the next meeting his bondsmen will be informed of his delinquency & he will not be considered a candidate for a new choice.

A Volume of Records Relating to the Early History of Boston Containing Minutes of the Selectmen’s Meetings 1811 to 1817 and Part of 1818. Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1908.

By March 17, he was out of a job. One can only speculate as to the reason for two years’ non-payment of accounts owing; my guess is poverty.

At some point, in the interval, he (and one assumes the family) had moved to Charles Street.

By August 11, 1814, William, Senior was dead, of “spasms,” age 49.

2. The maritime trader

Which leads us to the riddle of how and when William Henry McNeill, Junior took to the sea. The why of it seems clear enough — to support the family. At thirteen he was the breadwinner, with a brother age 10 and a sister not yet 7.

As to when, biographer Robin Percival Smith cites a passage in the log of the brigantine Burton for November 1828, where McNeill wrote, “I never (k)new it to blow harder at sea in my life which I have constantly followed for 14 years in different seas…”

Captain McNeill and His Wife the Nishga Chief, 1803-1850: From Boston Fur Trader to Hudson’s Bay Company Trader. Robin Percival Smith. Surrey/Blaine: Hancock House Publishers, 2001, p. 95.

Journal of a Voyage from Boston toward Bahia kept on Board Brig Burton by W. H. McNeill 1828 & 1829. Sunday Novr 16th 1828. BC Archives.

From this we might infer that he shipped out in 1814, the year his father died. The trouble with that scenario is that Boston’s shipping industry was pretty much shut down by combined effects of the US Embargo Act of 1813 and a British naval blockade of the New England seaboard beginning April 25, 1814.

Only five American and thirty-nine neutral vessels cleared … from Boston for foreign ports [in 1813]. On September 8 there lay idle in Boston Harbor, with topmasts housed and mastheads covered by inverted tar-barrels or canvas bags (“Madison’s night-caps”) to prevent rotting; ninety-one ships, one hundred and eleven barques and brigs, and forty-five schooners. And in December, 1813, Congress passed a new embargo act, which forbade all coastwise as well as foreign traffic, and was rigorously enforced. It is said that a man from the Elizabeth Islands, who brought corn to the New Bedford grist-mill, was refused clearance home for his bag of meal. Such a clamor arose against “Madison’s embargo” that Congress repealed it in the spring of 1814; but no sooner was this done than the British blockade was extended from Long Island Sound to the Penobscot.

The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783-1860 by Samuel Eliot Morison. Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1921, pp. 205-6.

The extended British blockade now clearly affected the volume of American trade, even when conducted in neutral vessels trading in and out of New England. Between 4 May 1814 and the peace, fourteen vessels attempting to reach Boston and other New England harbours from foreign ports were detained by the Royal Navy’s blockading squadrons and sent into Halifax Vice-Admiralty Court for adjudication. Over the same period, privateers sent in two more. Between 4 May 1814 and the end of the war, the Royal Navy took and sent into Halifax alone a total of 130 prizes, both neutral and American. Both the Boston Gazette and the Columbian Centinel reported that, by the end of the war, foreign trade shipping movements from New England’s major port had fallen to zero.

How Britain Won the War of 1812: The Royal Navy’s Blockades of the United States, 1812-1815 by Brian Arthur. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2011, p. 168.

In the face of such evidence, it’s more than likely that young William Henry McNeill did not ship out of Boston in 1814.

The privations Bostonians suffered in 1814 were, curiously, ignored by Smith, whose narrative focussed on the capture of the USS Chesapeake by HMS Shannon outside Boston Harbor the year before. He summons an image of the crowd gathering on Beacon Hill to watch the battle, where “nine-year-old William Henry McNeill … ran and shouted his excitement with his school mates, braving the punishment of absence from their master’s classroom.” We are told that McNeill “felt the pain of defeat and years later told his grandchildren about it.” (Captain McNeill and His Wife, 17, 19) Unfortunately, the biographer does not provide sources for these assertions. (One suspects that, like much detail in the book, they are his inventions.) Smith also perpetuated the error that McNeill was born in 1803 — which, to be fair, McNeill himself claimed in a deposition before the San Juan Islands boundary commission in 1871* — and draws from that the inference that he chose “a career at sea when only eleven years of age.” Smith does not, however, venture to suggest how the sea battle might have influenced McNeill’s choice of career.

* Great Britain, Parliament, Case of the Government of Her Britannic Majesty, submitted to the arbitration and Award of His Majesty the emperor of Germany. London, 1873. In BC Archives microfilm clippings file.

McNeill was on the North West Coast in 1816, according to George Blenkinsop, his son-in-law and colleague in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s posts at Stikine and Fort Rupert.* Given that ships usually departed New England in the fall, so as to round Cape Horn in the southern hemispheric summer, it’s possible McNeill’s first journey, likely launched in 1815, was bound for “the Coast.” The search for corroborating evidence for Blenkinsop’s claim yields nothing. Several ships in Howay’s List of Trading Vessels in the Maritime Fur Trade for 1816 meet the criteria of departure from Boston in 1815 and return in 1818. A likely one was the brig Panther, owned and operated by Pickman, Rogers and Ropes, which cleared Boston for “Liverpool and the North West Coast” on June 8, 1815, commanded by Isaiah Lewis; left Honolulu on April 22, 1816 “bound to the coast of North West America and first to Norfolk Sound [Sitka];” arrived there May 23; departed from Sitka in company with the fur traders Cossack and Atala in November; probably on the coast again in 1817; sailed from Canton on November 25, 1817; arrived at Boston on March 26, 1818.**

* George Blenkinsop, Fort Rupert V. I., letter to Capt. [John] Devereux Dock Master Esquimalt B. C. 25th May 1896, in Devereux correspondence file on location of Tonquin, BC Archives manuscripts catalog no. J/G/T61D; located by Richard Somerset Mackie and cited in his Trading Beyond the Mountains: the British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843, UBC Press, 1993, p. 134 and footnote.

** A List of Trading Vessels in the Maritime Fur Trade, 1785-1825, by F. W. Howay, edited by Richard A. Pierce. Kingston Ont: The Limestone Press, 1973, p. 115.

McNeill’s seagoing career resolves into three phases. About his apprenticeship, information is at best fragmentary.

His biographer identifies McNeill as the writer of the log of the Paragon beginning in January 1819 (Smith 28). The Paragon was owned by Josiah Marshall.*

* A List of Trading Vessels, p 141. According to Smith, the ship was owned by “Marshall and Wilde.” The master of the Paragon and, sometime later, partner of Josiah Marshall was Dixey Wildes.

The question of Paragon‘s ownership is problematic. In the online catalogue of the Bostonian Society, the Boardman and Pope account book 1811-1822, collection no. MS0048, lists “transactions” that “record purchases, renovations, and outfitting of various ships,” including “Paragon (1818).” There is a précis of the firm’s history: ” William H. Boardman (also known as Bordman) and Pascal P. Pope formed a business partnership to purchase and outfit ships for international shipments of various goods from Boston harbor. In business from 1807 to 1829.”

At the end of the log is W. H. McNeill’s signature, repeated several times as if for practice, followed by names of people and ships:

Journal kept on board the Ship Paragon, Dixey Wildes, master towards the Sandwich Islands … 13th day of January 1819. BC Archives.

Journal kept on board the Ship Paragon, Dixey Wildes, master towards the Sandwich Islands … 13th day of January 1819. BC Archives.

The logs of the Paragon cover the periods January to June 1819, when outbound from Boston to Hawaii, and March to May 1820, when returning from Canton, China to Boston. The second breaks off in mid-Pacific and is followed by the page reproduced above.

I’ve found nothing in the logs revealing of anything other than locational co-ordinates, weather and the activities of the ship’s crew.

The sum total of available outside information about McNeill during this period is as follows:

1. McNeill stated that “at 20 I became a master mariner” in his deposition to the San Juan boundary commission. That would have been in 1821 (following the known chronology of his life) or 1823 (following McNeill’s mistaken calculation of his age; also given in the biographical sketch in the McLoughlin Letters).

2. In February 1822, McNeill shipped aboard the brig Owhyhee in Oahu, bound for the North West Coast, as detailed in a letter from “Mr. Jones, Marshall’s agent at Oahu,” excerpted by Smith:

“Capt Grimes is pleased with the Brig [Owhyee] but complains much of the scanty way in which she was fitted out; he has been obliged to purchase here at an advanced price, cutlasses, pistols, boarding pikes, blunderbusses and other articles of defence, not an article for cabin stores, no sugar and nothing to drink but NE [New England?] rum. …

“A Mr Welty, long acquainted with the [Northwest] coast, and formerly an officer with Capt Grimes in the St Martin, will go Chief Officer of the Owhyee, Mr McNeil has shipped as second officer, for crew they will be obliged to take whoever they can obtain and those at advanced wages, a great mistake has been made in sending the vessel out so poorly manned, others on the coast will have much the advantage of Capt Grimes.”

Captain McNeill and His Wife, p. 32, no date or source provided. John Coffin Jones, Jr. was the agent of Marshall & Wildes in Hawaii— see “Boston Traders in Hawaiian Islands, 1789-1823” by Samuel Eliot Morison, in The Washington Historical Quarterly, 12:3, July 1921.

At least one scholar holds that William Henry McNeill was the captain of the Owhyhee on its maiden journey from Boston — see “Boston Men” on the Northwest Coast: the American Maritime Fur Trade 1778-1844 by Mary Molloy (Kingston, Ontario/Fairbanks, Alaska: The Limestone Press, 1998). Howay (A List of Trading Vessels, 154) identifies the master as William Henry, which corroborates a letter from Jones to Marshall in the Morison paper cited above: “I have the pleasure to advise you of the safe arrival of the Brig Owhyhee, Capt. Henry …” (Island of Woohoa, December, 23d, 1821, p. 191).

3. In December 1823, Capt Grimes wrote to Josiah Marshall, as excerpted by Smith, that

“My officers also wish to go home — McNeil would have stopp’d another season I think had not Capt Wilde (sic) written to him to come home, he is a smart young man and I am sorry to part with him at this time and think it would have been as well for him to have remained in the Brig and not to have gone home at this particular time.”

McNeill arrived at Boston aboard the Paragon on August 26, 1824. (Smith 47)

(Why did Wildes summon McNeill back to Boston? The answer may be germane to an understanding of McNeill’s advancement. Access to the apparently voluminous Marshall & Wildes inward correspondence housed in the Houghton Library at Harvard University was not possible within the scope of this chronicle; nor to the Marshall and Wildes Shipping Records 1822-1826 in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.)

The quoted correspondence suggest certain realities of the maritime trade in the Pacific. Hawaii was already a well-established base of operation for traders, specifically Massachusetts shipmen, that began in 1789 with the arrival of the Columbia, Captain Robert Gray. The “Boston men” soon took charge of the sea-otter trade; Hawaii became their winter headquarters. During the War of 1812-14, the trade with the Northwest Coast shrank dramatically for reasons already adumbrated. The number of American ships on the coast went from 13 in 1811, 12 in 1812 and 11 in 1813 to 4 in 1814.* Following the war, New Englanders manifested a fatefully expansive presence in Hawaii:

A new era opened in 1820 with the arrival of the first missionaries, the first whalers, and the opening of a new reign. It was the missionaries who brought Hawaii in touch with a better side of New England civilization than that represented by the trading vessels and their crews. But without the trader, the missionary would not have come. The commercial relations between Massachusetts and Hawaii form the solid background of American expansion in the Pacific, the fundamental influence that worked steadily toward the annexation of 1898.**

* Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841 by James R. Gibson, McGill-Queen’s university Press, 1992, Table 1, pp. 303-4.

** Morison, “Boston Traders in Hawaiian Islands,” p. 174.

Trading was no longer a matter of scooping up sea-otter furs from the Northwest Coast and flogging them for outrageous prices in Canton. In the post-war era, trading voyages required four or five manoeuvres to be profitable,

… involving the northwest coast, the Russian settlements, Spanish America, and the islands of the Pacific. From the ports of the United States, chiefly from Boston, vessels were sent to the Pacific with cargoes intended for sale in Spanish America or at the Hawaiian Islands. If the cargo could not readily be sold, it was often landed at Honolulu, either for later sale at that place or for transshipment to the coast or to the Russian posts. Having disposed of the cargo brought from the United States, the vessel either hastened to the coast to secure furs or took on board a cargo for Canton. The ultimate goal of the Pacific trade continued to be the market at Canton, where furs, sandalwood, and miscellaneous products from Spanish America or the South Pacific were exchanged for teas and silks. The success of the entire enterprise continued to depend upon the profits realized on the goods carried from Canton to the United States or Europe. Barring accidents, unexpected delays, or violent fluctuations in the markets at Honolulu, Canton, or Boston, this was a lucrative branch of commerce and one worthy of the daring and ingenuity of the commercial houses which dominated it.

The American Frontier in Hawaii: The Pioneers 1789-1843 by Harold Whitman Bradley. Stanford University Press, 1942; reprinted Gloucester, Mass: Peter Smith, 1968, p. 54.

In this new order, “the powerful Boston houses which had been the pioneers in trade along the northwest coast were no longer represented; in their place there appeared a new but no less energetic group of commercial houses, chief among which were Bryant and Sturgis, and Marshall and Wildes, both of Boston, and John Jacob Astor and Son, of New York.” (American Frontier, 53-4)

Growing competition and dwindling supplies of furs combined to make the Northwest Coast trade uncertain, such that, as agent Jones wrote to Marshall and Wildes in 1827, “The North West Ships have done miserable enough the last year — not 150 skins each, and what they have got cost an average Thirty Dollars. That trade is finished for the present, no object for more than two vessels in one season.” (quoted in Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods, p. 60)

On top of that, the Northwest Coast trade was dangerous. First Nations traders

The second phase of McNeill’s maritime career began when he took command of the Convoy in 1824. His travels are better documented

Do you know anything about McNeill’s rescue of the three Japanese sailors from the Makah, and of the porcelain from the Hojunmaru that McNeill brought down to Fort Vancouver, in 1834? Do you know if the McNeill family now own any pieces of this porcelain?

It’s not something I have studied. Primary source would be The Letters of John McLoughlin from Fort Vancouver, v 1, available as digital download for $50 on the Champlain Society website. Good summary narrative on HistoryLink, “First Japanese known to reach the future Washington state arrive in January 1834.” As for the porcelain, I will ask my family informants. Thanks for writing.

Hello Nancy: I have seen statements that the Makah Museum at Neah Bay has some porcelain from the Hojun Maru.

Hello, interesting article on the McNeill family ! Well done and bravo! Thought it might be worth mentioning that although I now reside in Europe, I spent part of my youth (I’m in my 60s now) in the Boston area and was once “drawn to the sea” myself. Enjoyed Vancouver back in 1974 when I was a (U.S.Navy) Midshipman on shore leave . Since my free Nimiz Library hours at the U.S. Naval Academy in the 1970s, I have been a fan of local history and of institutional history, especially that of the Marine Corps and the Navy. Like Captain McNeill’s brother, I went on to serve in the Marine Corps.

As you document so well above, Captain William Henry McNeill had a younger brother named Frederick Brush McNeill.

Born in Boston on November 8, 1803, Frederick and his mother (Mrs Rebecca McNeill) carried on an extensive correspondence with Massachusetts notables and with U.S. federal authorities from 1819 until 1822 when Frederick B. McNeill (sometimes written “McNeil”) was admitted to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, as a Cadet from the state of Massachusetts. (US Military and Naval Academies, Cadet Records and Applications – now available on Ancestry.com).

After failing to qualify for a nomination in 1819, 1820, and 1821 for membership in the Classes of 1823, 1824, or1825, Captain William Henry McNeill’s younger brother Frederick was overjoyed at his acceptance as a member of West Point’s Class of 1826.

He mentions (in his April 1822 letter of acceptance) his good fortune in light of the fact that he “was just back in Massachusetts” from a sea voyage. It would be interesting to discover how much sea service the younger McNeill had accumulated by that time and whether or not he had sailed with his older brother.

Frederick B. McNeill’s subsequent army career was less than happy. Warranted a Cadet (4th Class), U.S. Army to rank from July 1, 1822, Cadet McNeill ranked 52nd after West Point’s midyear examinations in January 1823. In January, 1824, not having been examined on account of illness, he missed promotion and was retained as a member of the 4th class, being turned back into West Point’s Class of 1827. In 1825 he advanced to Cadet 3rd Class with the Class of 1827, but an act of misconduct brought about a general courts-martial (GCM) and Cadet Frederick B. McNeill was dismissed from the Army and from West Point on January 9, 1826. (Registers of the Officers and Cadets of the U.S. Military Academy from June 1822 through June 1826).

Normally a courtmartial conviction would have barred Frederick B. McNeill from any further U.S. federal appointment or employment, but the times were different and there is perhaps more to discover.

From 1826 until 1834 there is a gap.

Did he return to Boston ? Did he serve an enlistment in the U.S. Army the way Edgar Allan Poe did ? Did he serve in the Merchant Marine or in the Revenue Marine?

In 1834 the Massachusetts-born Frederick B. McNeill received a U.S. Congressional appointment as the first U.S. Marine Corps officer to be commissioned from the state of Alabama. Throughout his subsequent Marine Corps career, F. B. McNeill was carried on the rolls as “a citizen of the state of Georgia”.

Ordered to HQ, United States Marine Corps at “8th and I” above the old Washngton (DC) Navy Yard, for officer indoctrination, 2ndLt F.B. McNeill’s commission was dated 17 October 1834 and he was ranked 6th of the 10 new lieutenants who completed the course of instruction.

Lieutenant McNeill then embarked on an honorable, if not overly distinguished career in the Marines.

Promoted to 1stLt, USMC, to rank from 15 April 1841, Lieutenant McNeill was at sea in command of shipboard detachment of Marines when the Mexican War began. Although he was not nominated for a Brevet in 1848, he was retained on the active list in good standing that year when officers senior to him were dropped from active duty in service reductions.

F.B. McNeill advanced to the rank of Captain USMC, to rank from 19 August 1855, at a time when the U.S. Navy Department was continuing to reduce and streamline its effectives. A New York newspaper reported his death on Monday March 17, 1856, as having occured on Friday March 7, 1856. Chronically ill and on sick leave for some time, Captain McNeill’s death was reported to the U.S. Navy Department as having taken place on March 13, 1856, in Philadelphia …

Many thanks for your informative post about Frederick McNeill. Any idea where Brush figures in the family lines? As to Frederick’s interval at sea, it doesn’t fit with William’s whereabouts — he was in the Pacific from 1820-24. But he may well have given F a leg up with his employer Marshall & Wildes.

Thank you for some interesting information. I have just begun to search my family history. Mcneill is an ancestor of my family. My great grandfather John Lee Johnston married Catherine Rebecca Young who was the daughter of Fanny (one of mcneill’s Daughters)

Interesting line! Sisters married brothers. Any idea how that happened? My information is spotty about that line. And there is the tragedy of Fanny’s disappearance sometime after their fourth loss of a little child.

oop not legible … will send in an email …

This is a branch of our family that has mystified me for years! Catherine Rebecca Young and Amy Georgina Young , daughters of James Judson Young, brother of my great grandfather George. Our branch of the family came to Australia.

Every now and then I go looking for Fanny….

I descend from William McNiell Jr’ son, George F. McNiell. I met some relatives on ancestryDNA. My native great great grandmother was pregnant with my great grandmother, Elizaneth McNiell, when he was u foryunately murdered. I am just learning. Please do not hesitate to email me 🙂 qaaditee@gmail.com i do have photos to provide. 🙂

I am looking to locate the archives that hold WM H McNeill’s Journals from 1833 – 1837, would you know where they are located? They are not in the BC Archives.

Thank you!

Have you searched the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives? If there are logs of the Lama, the originals would be there, I’m guessing, and you can order microfilm copies through your public library. Otherwise, I seem to recall that some of the ships’ logs written by WHM are not catalogued online but may be found in the old card catalogue near the NW corner of the BC Archives reading room. Hope this helps …

Thanks, I’ve already tried both HBC and the BC Archives to no avail. Was wondering if some of McNeill’s journals may have landed in another archive elsewhere…

Captain McNeil is my GGG Grandfather and his son Alfred is my GG Grandfather

Hi I am trying to complete my family Tree.

My grandfather was Alfred McNeill who died in NY.

My Dad is Alfred McNeill too. I know my Great Great Grandfather lived out west. Would love to know if anyone knows either of them.

I have seen a photo of Matilda, Martha McNeill, She was wearing a black dress and looking sideways, in an oval frame, She is my 4th.

great grandmother. She was married to Capt. W.H. McNeill. I believe it was taken at Fort Simpson

Are you able to share that photo?

Mathilda was his first wife, from Kitladamax, his second was Martha of the Nass tribe

Matilda was from Kitladamax? Would be interested to know your source. According to Dr. Helmcken’s Reminiscences (1975), “Mrs. McNeill was a very large handsome Kigani [ie Kaigani

Haida] woman, with all the dignity and carriage of a chieftainess, which she was.” He was present at her death in 1850 at Fort Rupert.

Would you know where or if thereis a marriage certificate for Captain William Henry McNeil and Mathilda? According to records they were married in British Columbia in 1828. Any known facts where in BC they were married?

Greetings Yvonne, thank you so much for your response, its been awhile since I have been on this site. I am Matida’s GGG granddaughter and would love to connect as I am not sure where Kitladamax is? Matilda’s father was likely Chief Cowhoe but we know little about Matilda.

some of his ledgers are in England, Marine history as noted by my grandmother Edna McNeill Janak [ she was McNeill’s greatgrand daughter,

I have just discovered this website! I am the GGG granddaughter of William Henry McNeil and his wife Matilda (Haida). I descend from Alfred McNeil (1837) their son and have done extensive work on my family. Martha Mcneil was his second wife after Matilda died giving birth to twin daughters Rebecca and Harriett Mcneil. Martha (second wife) and Mcneil had no children.

I am happy to share what I have!

Alfred, my GG Grandfather lived and was a pioneer in Vernon BC and married Susan George and had five children.

Do you know if there is any relationship with either of these 2 wives to Margaret Snaach from Fort Nass/Simpson who married Donald MacAulay (Macaulay)? MacAulay travelled with McNeil and worked for HBC

One history record says McNeil married their oldest daughter – Mary (alias Martha??) in June 1853

I am curious as my gr gr grandmother is Margaret Snaach.

their daughter Flora married John Tod’s son, James. John Tod settled in Oak Bay when he retired from the HCB, prior to McNeil. They were neighbours.

Sorry to say I know but a little about Donald Macaulay. Your ancestor was “probably from the Tlingit tribe on the Tongass River,” according to an article “Bailiff Macaulay” by C. Hanna in the BC Historical News, Winter 1992-93 pp 16-19.

Mary Macaulay married William McNeill, the son of Captain McNeill, and they raised ten children while farming his father’s property. Eventually Capt McNeill and his second wife Martha, aka Neshaki, retired to another corner of the property.

So the answer to your question about your ancestor’s possible relationship to Capt McNeill’s 2 wives, is probably: related by blood, neither; by marriage, both.

Hello,

Yes, Mary Macaulay married William McNeill Jr, Mary was the daughter of Donald Macaulay and Margaret Snaach.

I would like to learn more about Margaret Snaach, as she would have been my Great, Great, Great grandmother.

MARRIAGES solemnized in the Parish of Viateria in the County of Vancouver Island

– in the Year 1853

William MS Neill

native of Fort Simpson, N. W. Const of America. and Mary. Macaulay nature of Fort Simpam,

N.I. Const 5f America

were married in this

Fort by loans

of Victoria Parish-

_of Victoria Parish-

with Consent

this thurd

Day 아

June

-in the Year One Thousand eight hundred and fifty Have

By me. Robert John Staines A.B. Aul: Poin Cantat

William MSNaill

This marriage was solemnized between us

har

– Many X.

mare

„Macaulay

In the Presence of

Donald Macaulay

고

Fly

Andrew Muir

I agree she was Kaigani Haida from Dall Island.

W.H. McNeill, Obituary, Victoria Daily Colonist, 5 Sep, 1875.

Died yesterday, ie 4 Sep; “… Capt McNeill came to the coast when a boy in 1816 from China. In 1826 he returned in the brig Convoy, a trader for a Boston fur company. He joined the Hudson Bay Company in April of the year 1832, and retired from the service about ten years ago. He was a very energetic man and was always highly respected by his fellow officers in the colony and the citizens generally. His last service was commanding the steamer Enterprise from which he retired about a year ago. He was a native of Boston, Massachusetts, and witnessed the naval fight of 1815 between the U.S. frigate Chesapeake and the British frigate Shannon, from the heights of Boston. The Captain leaves a large family to mourn his loss.”

Bruce McIntyre Watson 2010: 676-7

McNeill, William Henry (c. 1801 – 1875) (American)

Birth: Boston, Massachusetts – c. 1801 or 1803

Death: Victoria, British Columbia – September 4, 1875

U.A. Officer, Paragon (ship) (1819 – 1820); HBC Captain, Convoy (brig) (1824 – 1825); U.A. Captain, Tally Ho (brig) (1826); Officer or log keeper, Golden Farmer (whaler) (1827 – 1828); Captain, Burton (brig) (1828 – 1830); HBC Captain, Lama (brig) (1830 – 1837); Captain, Beaver (steamer) (1837 – 1840); Captain, Cowlitz (barque) (1842 – 1843); Chief Trader in charge, Fort Stikine (1845 – 1848); Chief Trader in charge, Fort George [Astoria] and Cape Disappointment (1848 – 1849); Chief Trader and superintendent of construction, Fort Rupert (1849 – 1850); Chief Trader, Columbia Department (1850 – 1851); Chief Trader, Fort Simpson (1851 – 1856); Chief Factor in charge, Fort Simpson (1856 – 1857); Chief Factor in charge, Fort Simpson (1861 – 1863).

William Henry McNeill started his sea-going career as an employee of Boston traders sailing between the Sandwich Islands and Boston. On October 26, 1824 he left Boston harbour in command of the Convoy, arriving back in Oahu the following year. By 1826, the command of the Convoy was given to John Dominis who along with McNeill, now in command of the Tally Ho traded at Norfolk Sound for the season. From 1830 he sailed the Lama from Boston and the following year was back on the Northwest Coast. In 1832, when McNeill brought the vessel to the Coast and heard from Dr. McLoughlin that the HBC was in search of such a vessel to replace the unserviceable vessel, Vancouver, he quickly sailed to the Sandwich Islands where the Lama was purchased by Chief Factor Duncan Finlayson. Following this, on September 1, 1832, McNeill was hired on by the HBC in Oahu, an act to which the Governor and Committee reluctantly agreed, preferring an American to the incompetent English captains. In the early summer of 1834, McNeill ransomed three shipwrecked Japanese from the Cape Flattery Makah. In 1837, in command of the steamer Beaver, he found Victoria harbour a site which later that year McLoughlin rejected. In January 1838, when the crew of the Beaver mutinied against McNeill’s discipline, John Work had to bring the vessel from Fort Simpson to Fort Nisqually with McNeill as a passenger. At that point he was ready to retire in 1838 but a promotion to Chief Trader in November 1839 induced him to stay on. In 1846 in response to the establishment of the international border, McNeill along with sixteen others, laid claim to 640 acres [259 ha] (one square mile) [2.6 sq. km] of land around Fort Nisqually, land to which the HBC/PSAC held possessory rights, a claim which never came to fruition. In 1849-1850 he superintended the construction of Fort Rupert and in 1854 he purchased a town lot in Victoria and in 1855, over 250 acres [101.2 ha] in the Victoria district. He took charge of Fort Simpson for eight years and became Chief Factor in 1856. When in 1861 he returned to the coast after a year’s furlough, he was put in charge of Fort Simpson for two years before retiring. He settled on a farm near Gonzales Point, Vancouver Island and in 1869 added his name to a petition to U.S. President Grant asking for annexation of British Columbia to the United States. For a time before his death in 1875, he commanded the HBC’s steamer Enterprise.

William Henry McNeill had two wives and twelve children. Around 1831, he married his first wife, Matilda/Neshaki (?-1850), a Kaiganee Haida. Nine of their children were William (?-?), Harry (?-?), Alfred (?-?), Helen (?-?), Lucy (?-?), Matilda (?-?), Fanny (?-?), Rebecca (c.1850-?) and Harriet (c.1850-?). Matilda died in 1850 from complications after having given birth to twins. On January 15, 1866, McNeill married Martha (c.1826-1883), a Kinnahwahlux Nass, at St. Paul’s Church, Metlakatla, B.C. Martha died October 4, 1883 at the age of fifty-seven.

PS: CU-B Inore/Eagle; BCA log of Convoy; log of Paragon; log of the Lama; HBCA YFDS 5a-7, 13; FtVanASA 3-8; YFASA 12-15, 17-19, 24, 27-32; FtVicASA 1-12, 14-15; FtVicCB 23; FtSimp[N]PJ 3; BCA BCGR CrtR-Land; BCGR-AbstLnd; PSACFtNis; BCCR CCCath; BCGR-Marriage; BCGR-Deaths; 1869 Victoria Directory, p. 38; Van-PL Colonist, Oct. 6, 1883, p. 3 PPS: HBRS VII, p. 314-18 SS: Howay, A List of Trading Vessels; Pierce, Russian America, p. 347-48

Trying to get my status card, as Fanny McNeil was my dads (Ronald Lee Johnston) great grand parents. Fanny McNeil was one of Captain Mc Neil’s daughters. Captain McNeil was married to Matilda ( Kaigani Haida Cheif) . Any info would help. Thanks Colleen Johnston.

If you collect enough identification could you please tell me how to go about this? Thank you so much

Pole erected in front of the house of Wey-kla-ka-las at wasam.

Figures (from top to bottom):

Thunderbird

European figure (Matha Hill)

adopted as a crest by the ancestor of Wey-kla-ka-las

Beaver

European figure (the guardian of

Matha Hill)

Wolf

European figure (another of Matha

Hill’s guardians)

Dzo-no-qua

The pole is believed to have been carved By Omagis and Kla-kwat-se in the 1890°:

Who was ‘Matha Hill?

Totem Pole Figure

Mystery No Longer

Look up this news paper article.

Or email me and I can share it.

Ross. Bay Cemetery

I have found the following information for you with regard to your plots at Ross Bay Cemetery.

Block B, Plots 89 West of Road 33

William McNeill (1482) Born and died in Victoria October 29, 1889 at the age of 59 years,

There is room for 8 more sets of ashes in this plot.

Block B between Plots 89 and 90 west of Road 33

Robert Albert McNeill (7291) born and died in Victoria, January 31, 1908

at the age of 29 of heart failure. He is buried at 71/2 feet Donald H. McNeill (16918) born and died in Victoria January 14, 1928 at the age of 74 of Heart/bronchitis. He is buried at a depth of 6 feet.

There is room for 8 more sets of ashes in this plot.

Block B Plot 90 west of Road 33

Mary McNeill (8694) born and died in Victoria, September 18, 1911 at the age of 72 of Uracmia. There is room for 8 more sets of ashes in this plot

Block B between Plots 90 and 91 west of Road 33

Helen F. McNeill (22220) born and died in Victoria on March 27, 1948 at the age of 73 years of Coronary thrombosis. Buried at 6 feet. There is room for 8 more sets of ashes in this plot.